Amplify your reach and drive results with our tailored paid media strategies.

If you are anything like me, you watched The Queen’s Gambit and now fancy yourself a learned chess player and scholar. As such, Google’s announcement that responsive search ads, or RSAs, are now the default ad format in Google Ads reminds me of a very particular chess tactic: the quiet move.

A quiet move is a move that does not a capture, check or immediately threaten the opposition. As of this writing, Google’s move to make RSAs the default ad format only amounts to a change in the UI, where Google will prompt advertisers to create an RSA instead of an ETA when first building an ad group. ETAs can still be created and RSAs can be ignored.

On the surface, nothing gained and nothing lost—but quiet moves are designed to incrementally improve one’s position, make an attack easier to mount, and more effective when one does. If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to continue to look through Google’s changes with an eye on their endgame.

A chess opening is the early stage of a game where each player seeks to develop their pieces and pawns in a way that will be advantageous once the action starts to mount. Advertisers and Google have been jockeying for position for years.

Google launched Enhanced Campaigns in 2013, removing device-specific campaigns but adding the ability to bid based on contextual signals like location and device. For those still indulging my chess analogy, this was e2-e4, a strong and classic opening.

From there, Google brought bid strategies into the platform, added an additional ad slot above organic listings, created Dynamic Search Ads, removed average position reporting and bidding, added feed-based shopping listings, expanded text ads, introduced optimization scores, conducted a recent match type update, removed long-tail queries from SQRs, added automated location extensions, and, of course, unveiled responsive search ads.

For every automation, advertisers have steadily countered the loss of control with defensive moves like negative pathing, location-specific campaigns, and even the way broad match modified keywords were used in the industry. Ng1-f3, Nb2-c6, Bf1-c4, and so on and so forth. Development of pieces that we all believed gave us the best chance to win, or at least survive until the endgame.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

That brings us to the latest announcement. Google made a small move that did not attack advertisers’ ability to run search campaigns. It did not remove manual bidding, like Microsoft announced last week. It did not replace keywords with categories or audiences. So what did the search giant actually do? It grabbed space and made its next inevitable moves all the easier to execute.

Digital advertising is often stuck in a paradox. Automation and machine learning is the only solution to the ever-burgeoning complexity of the industry—and though strategists and tacticians praise the tech, they also bemoan the loss of control and human influence. Google’s advances in automation have undoubtedly made paid search management easier to execute, on average, but harder to execute well. A mentor of mine once told me that Google has a sort of Hippocratic oath: instead of “do no harm”, it’s “give no advantage”.

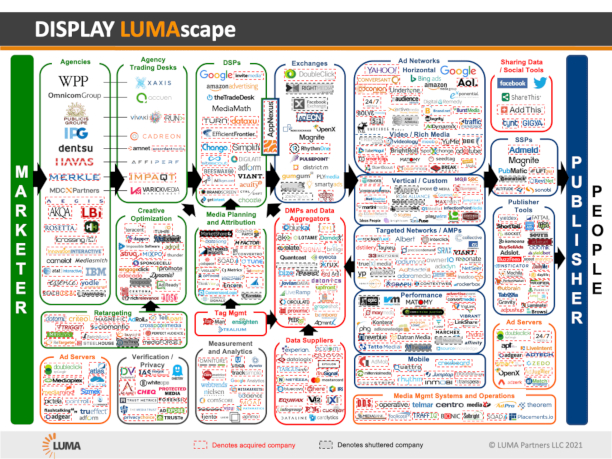

Credit: LUMA

Google telegraphed its intentions a few years ago when it removed the “word” from Google AdWords. Search campaigns will eventually be wholly built, bought, and optimized towards user intent and the phrases that are searched will simply be an input rather than an endpoint.

The move to elevate RSAs to the default ad type will undoubtedly increase their usage, especially amongst smaller advertisers. That change will begin to erode the +5% to 15% increase in clicks and conversions Google touts for RSAs vs ETAs as more and more advertisers are using ad copy that shifts and bends to fit every single auction.

The solution that Google will push is broad keywords with smart bidding, one step away from bidding on categories and, later, stages of the consumer journey. This is the endgame, where search campaigns are always on and always serving to prospective customers regardless of their current use of Google.

Is it a stretch to envision a SERP where positions one and two are related to the current search and slots three and four serve ads against whatever category a user is closest to conversion? It would increase competition for every spot and line up with everything Google has done so far. That apoplectic feeling when looking back at a finished chess game and wondering, “How could I have not seen that move coming?” is essential to getting better, but never feels good in the moment.

To be clear, making the quiet move of shifting the default ad type does not directly lead to the future I detailed above, but that’s the entire point of a quiet move. While that future may still be a ways off (or it may not be…), Google’s move tells me that its endgame is starting to take shape. Savvy advertisers would be wise to start plotting their countermoves.

Amplify your reach and drive results with our tailored paid media strategies.

Amplify your reach and drive results with our tailored paid media strategies.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.