How-to-respect-data-privacy-in-the-...

How-to-respect-data-privacy-in-the-...

In today’s fully digital world, new laws such as GDPR in the EU and the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (which goes into effect in 2020) aim to allow consumers to not only opt out of data capture but also have more control over their data and how it’s used.

In theory, this type of legislation will reduce the sophistication of targeting that digital marketers have come to rely on, and remove or reduce the prevalence of advertising that relies on personal data. With that in mind, let’s review these two laws and learn how marketers can remain compliant as they strive to address consumers in a relevant, personalized way.

What is GDPR and how does it affect marketers?

Although GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) is EU law, its impact is being felt by marketers across North America. It is a wide-reaching privacy act with very strong language regarding personal data, which it defines as any information related to a natural person or ‘Data Subject’ that can be used to directly or indirectly identify the person. That means any information—even something as seemingly innocuous as the capture of IP address—is in the crosshairs of GDPR.

Any captured user data must also be made available to the consumer on request (meaning it must be in a format that makes sense and is readable by humans) and consumers must be able to opt out. This is no small feat: prior to GDPR, many of these data points did not readily exist in a single location in a format that could be tidily boxed up and handed over to a consumer.

Perhaps most alarming development for marketers is that non-compliance with GDPR comes with a stiff penalty: those found in breach of its rules can be fined 4% of annual global revenue or €20 million (whichever is greater). Clearly, these compliance factors coupled with the large fine required most EU marketers to address them prior to its in-effect date of May 25, 2018. Indeed, anyone who had EU visitors to their website, or who targeted European users with media, needed to ensure they were compliant—even if they, the marketer, were based outside the EU.

GDPR has changed everything—and nothing

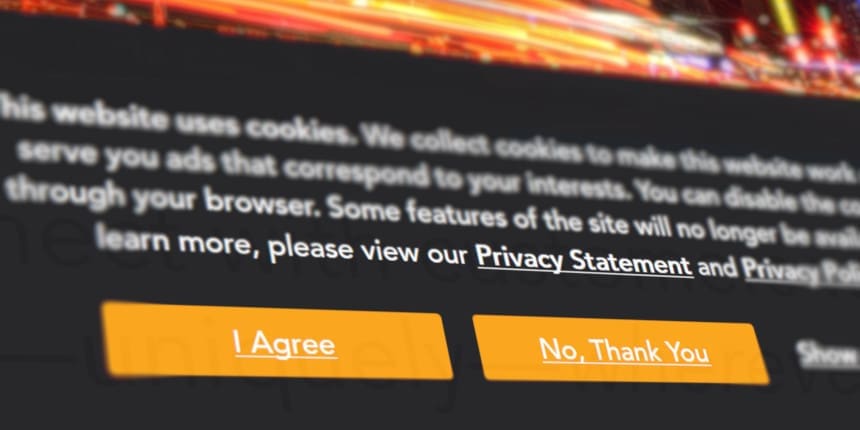

Reading this you might assume that the major data-holding companies such as Facebook, Google, and others of their kind were slapped with enormous fines in the days following GDPR’s introduction. Well, in short, no. Though there were complaints filed against Facebook, Google, WhatsApp, and Instagram almost immediately, nothing significant of note has occurred since. What did happen, if you were paying attention, is that nearly every global website suddenly featured a “we use cookies” pop-up bar with a link to its (updated) privacy policy.

As a user, on most of these websites, you can simply click “I accept”, close out of the pop-up, or even ignore it if it doesn’t bother you. And guess what most people do? They click “I accept” or close out of it because they want their content. Jeff Bezos got to the heart of this behaviour in his 2018 Letter to Amazon Shareholders:

One thing I love about customers is that they are divinely discontent. Their expectations are never static—they go up. It’s human nature. We didn’t ascend from our hunter-gatherer days by being satisfied. People have a voracious appetite for a better way, and yesterday’s ‘wow’ quickly becomes today’s ‘ordinary’.

We have grown so used to these privacy policies and terms and conditions that we’ll blindly accept or close out of a privacy policy pop-up to continue our quest to get to what we’re after. Want to continue using one-click ordering, sharing your stories on social media, monitoring your exercise habits, and consuming ad-supported content? Accept, and move on.

CCPA: The first of its kind in the US

Because of this persistent data collection—or perhaps simply because of the notion that somebody needs to protect users from themselves and their now-ingrained behaviors—California has become the first US State to address privacy head-on with its own version of a personal data protection law.

Though not quite as demanding as the language of GDPR, the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 states that users have the right to know what information companies are collecting about them and why, and learn what partners (if any) they share that info with. As a consumer, you will have the option to stop companies selling your data and compel them to delete data they have already collected. It also has provisions for data collection on children under the age of 16.

It is interesting to note that the CCPA went from a draft to a law in about a week. It was actually a response to a more sweeping ballot measure that would have been even more restrictive—and would have made it easier to bring legal action against companies that were non-compliant with consumer requests for privacy. Unsurprisingly, giants like Amazon, Google, Facebook, Twitter, and AT&T lobbied against the more restrictive ballot measure.

It’s interesting to note how these companies talk about privacy. Tim Cook of Apple, one of the companies that lobbied against the ballot measure, had this to say in October of 2018:

We at Apple believe that privacy is a fundamental human right. But we also recognise that not everyone sees things as we do. In a way, the desire to put profits over privacy is nothing new… These scraps of data… each one harmless enough on its own… are carefully assembled, synthesized, traded, and sold… Taken to its extreme, this process creates an enduring digital profile and lets companies know you better than you may know yourself…

We at Apple are in full support of a comprehensive federal privacy law in the United States. There, and everywhere, it should be rooted in four essential rights: First, the right to have personal data minimised. Companies should challenge themselves to de-identify customer data—or not to collect it in the first place. Second, the right to knowledge. Users should always know what data is being collected and what it is being collected for. This is the only way to empower users to decide what collection is legitimate and what isn’t. Anything less is a sham. Third, the right to access. Companies should recognise that data belongs to users, and we should all make it easy for users to get a copy of… correct… and delete their personal data. And fourth, the right to security. Security is foundational to trust and all other privacy rights.

Confusing, isn’t it? Apple ostensibly wants a privacy law but lobbied against a privacy law that it deemed too restrictive. If even Apple doesn’t have a definitive stance on where, exactly, to draw the line, how can any marketer approach this in a safe, smart way while still providing the relevant, personalised experiences their customers have come to expect?

How to get ready for CCPA

We believe there are five critical initiatives marketers should undertake to prepare for CCPA:

- Any marketer that captures individual PII (personally identifiable information) must ensure they have received a firm opt-in from the end user (e.g. email opt-ins; text opt-in, etc.). It will not be enough to assume opt-in as a result of not having an active opt-out.

- “Sensitive” data such as credit or medical history, for example, should not be used for any type of advertising profiling or targeting without explicit permission from the user that they want to receive this sort of targeted communication and are aware that the marketer holds this information.

- Marketers that capture customer data must have clear and obvious privacy policies outlining what data they collect and how they use it.

- Marketers must have a data governance strategy that ensures proper handling of any collected data, and is built to be able to let consumers know how they’ve used their data and to allow them to permanently opt out.

- Ensure all media partners and vendors you use have appropriate compliance in place. If they do not, we recommend that you do not buy media or deploy them in order to limit liability.

GDPR is yet to have any major negative impact on the largest of the data-collecting companies—and CCPA will not go into effect until 2020—but marketers are strongly recommended to take all these steps to ensure compliance now.

And, who knows? Given that the largest corporations are actively involved in open conversation about how to protect user privacy, perhaps this new legislation combined with the “mega” companies’ cooperation will actually change how users interact with brands in the not-so-distant future.

Want to know how to navigate complex new privacy laws and target your customers in an ethical, responsible way? Then it’s time to talk. Speak to DAC digital experts today!