Theartofnativeadvertising-2

Theartofnativeadvertising-2

Part one of this two part series will provide a working level understanding of native advertising – what it means, what it looks like and why it improves performance. In part II, we will apply this understanding to help uncover and instil best practices when crafting a native ad.

As digital marketing continues to evolve, traditional display tactics have slowly been losing their luster. Some argue that through advancements in technology and growing negative consumer sentiment towards banner ads, their success rate has dropped significantly. Recent studies have revealed an average click-through rate of approximately .07%. As organisations demand higher ROI’s on their marketing budgets it can be difficult to continue to convince buyers that the juice is worth the squeeze. In order to win back marketing pounds, the industry has had to be innovative in its offerings. One such innovation is native advertising.

What does native advertising mean and what does it look like?

In the early days of the ‘wild west’ that is paid digital media, it was difficult to determine what this new term really meant. Without proper definition agencies were free to slap the word on anything that remotely resembled a native advertisement. All of this action with no real direction lead to confusion in the industry. In order to give native ads, a fighting chance buyers had to understand what people were referring to. So, industry experts set out to resolve this problem.

In December 2013, the IAB set parameters around what constitutes a native advertisement. In order for something to own the title it must adhere to two guiding principles:

Form – native ads must match the visual design of the experience they live within, and look and feel like natural content.

Function – native ads must behave consistently with the native user experience, and function just like natural content.

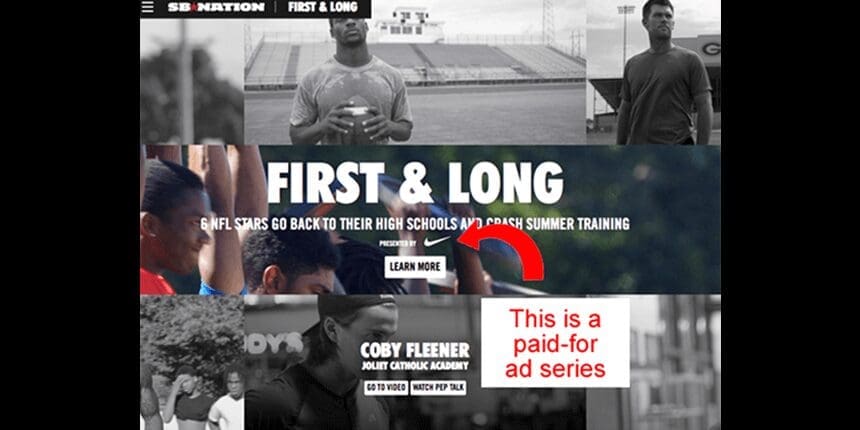

There are also expectations regarding acceptable amounts of disclosure. Because the execution is intended to seamlessly integrate into its environment, it has the potential to blur the lines between editorial and paid content. Therefore it should be very explicit that what the viewer is engaging with is being promoted on behalf of a brand. This can be accomplished through the use of logos, terms such as ‘brought to you by’ or ‘promoted by’ and listing the company name.

In other words, native advertisements should not overwhelm the viewer or be disruptive. They must engage the user in a way that feels like it belongs there.

Why natives ads are effective (the science behind it all)

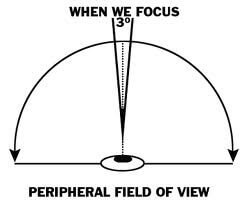

Native advertising works because of three key factors – where they lie in our field of vision, their ability to capture the reader’s attention and something that I like to call the ‘agitation factor’.

Our Line of “Site”

It has been proven that humans have a limited ability to focus on more than one area at a time. Static images in our peripheral view are very hard to process. This is a key failing of traditional display ads – because they are placed on the borders of a screen it is very difficult for anyone to process the contents of an ad while focused on something else. By placing native ads in the line of sight of a reader it is more visible and therefore has a higher potential to be read.

The Power of Processing

When something is read vs. seen it has a greater impact on a consumer. This is another key feature of native advertising. Instead of just glancing over a display ad the act of reading it forces us to process it more thoroughly. This means that as marketers our message has a greater likelihood of ‘sticking’ with the consumer and influencing their behaviors.

Pardon the Interruption

The third and final reason, though not technically named the agitation factor, is just as significant as the others. Because native advertising matches the look and feel of the article it is less disruptive. For the ones that are placed at the beginning or end of an editorial, they give the reader the choice to engage it after consuming or before starting something new. Properly leveraging native ads ensures that your brand does not earn a reputation for interrupting online experiences and the drop in conversions associated with it.

How many formats can native advertisements take?

Even within the parameters set out by the IAB, native advertisements are versatile and can be used in many different ways. The most common types are:

- In Feed Units – they appear in the natural flow of an article or feed. It is common to encounter this style in apps, on mobile and in editorial. They share similarities with promoted listings as they should identify who is sponsoring the in feed content

- Recommendation Widgets – these appear at the end of an article or section and provided promoted recommendations based on search behavior

- Paid Search Units – these appear on search engines and are the most familiar form of native advertising. They provide a website, description and ad copy (usually) related to the specific query

- Promoted Listing – these are very similar to paid search units but they can appear deeper in a feed than the traditional bottom and top page paid units. They usually promote a specific product

- In Ad With Native Elements – the look and feel of the ad is traditional but the content is contextually relevant and follows the same presentation when clicked on

- Custom – those that fall outside of the neatly packaged categories listed above but that theoretically follow the native advertisement framework.

Putting it all together

A lot of ground has been covered so far but sometimes a picture can say a thousand words. Below is a comparison between traditional display ads and native ads to help illustrate the differences:

In this example, there are two instances of traditional banner ads – at the top beside Mashable and in the bottom right corner from Intel. Both do not have the look and feel of the editorial. They do not flow with the article and are not in the reader’s direct area of focus.

In comparison, this example contains the necessary components to be classified as an in-feed native advertisement – it feels like it belongs, it is easily identifiable as a paid advertisement, it has engaging content and it is in the readers direct line of sight.

In a future installment, we will analyse effective ways to implement this type of advertising into a marketing campaign. Contact DAC today for more information!